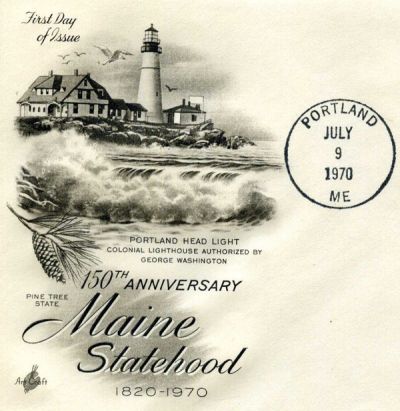

Primary Source

INDEPENDENCE OF MAINE

Portland, March 21 — Thursday last witnessed the birth of a new State, and ushered MAINE into the Union. The day was noticed, as far as we have heard from the various towns, by every demonstration of joy and heart-felt congratulation, becoming the occasion. In this town salutes were fired in the morning, at noon, and at sunset — the independent companies were under arms, and appeared in their usual style of military excellence — the ships in our harbour displayed their flags — the Observatory and adjacent buildings were brilliantly illuminated in the evening, and the celebration closed with a splendid ball. Gen. King, President of the Convention and acting Governor of the State, was in town making some necessary arrangements for the new government, and honored the company at the ball with his presence for a short time in the evening. He left this town on Friday — and was met at Brunswick by a large number of military officers mounted, together with a detachment of cavalry, and escorted to his seat in Bath.

Union Hall, in which the ball was held, was filled to overflowing with all that Portland can produce of elegance and fashion and beauty; its walls were decorated with national and military colors, tastefully festooned, giving a rich appearance to the room, and filling the soul with enthusiasm and patriotic feeling. In front of the orchestra, our national armorial, an eagle, lately killed in this neighborhood, spread his capacious wings, bearing on his breast a brilliant star, [signifying] the addition now made to our national constellation.

May the day, which has so auspiciously commenced our political existence as a State, long be remembered with complacent feelings, and every annual return bring with it, by the many blessings it may produce, additional inducements for its celebration.

New England Chronicle, March 21, 1820