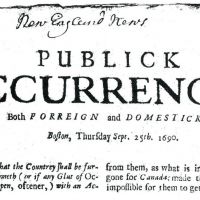

Primary Source

Boston Globe, Vol. 1, No.1.

SALUTATORY

These preliminary remarks will introduce the general plan of THE BOSTON DAILY GLOBE, showing its peculiar purposes...

The columns of THE GLOBE will be devoted to the intelligent and dignified discussion of political and social ethics and current events at home and abroad, with a minute and careful review of commercial and financial matters, and a comprehensive report of the various markets of the world. The fine arts -- music and the drama, sculpture and painting, with all important new books, will receive ample and judicious attention from experienced individuals. Its correspondence will be a marked feature of the paper, and will be conducted by able and responsible persons, stationed at the most important points in Europe and America, and thorough whom we design to impart a special interest and value to these columns. The well-digested purpose is to produce a first-class national journal, and though the consideration of local matters will ever form a prominent feature of THE GLOBE, yet its scope is designed to impart universal interests by the temperate and intelligent discussion of such subjects as demand the consideration of the great mass of the people. To accomplish these ends, its editorial corps has been carefully selected and embraces such varied ability as will render its daily issues, in this respect, second to no newspaper in the country...

NEWS IN BRIEF

- The steamship Japan sailed on Friday from San Francisco with $1,433,000 in specie;

- Kansas has abolished the death penalty for murder, reserving it only for horse thieves under the jurisdiction of Judge Lynch;

- Minority representation is approved under the Utah Constitutional Convention; that's to give husbands a chance of making themselves heard;

- There is a party of Japanese, consisting of seven men, now stopping at the St. James Hotel in this city;

- Our correspondent writes us from Washington that there is an average of 1,000 patents granted monthly by the Patent Office at the present time;

- An apothecary's clerk delivered a fatal dose by mistake in New York last Friday. There are few more responsible positions than that of a dispense of physicians' prescriptions;

- A passenger by the Pacific Railroad who arrived in Boston yesterday, and who understands these matters, expressed grave doubts about running these cars in winter...

... - Over one million children, it is said, attend the public schools in the New England states, a most encouraging statement...

- Spanish mackerel, considered a game fish, and as belonging exclusively to southern waters, are now nearly as common here as elsewhere:

- Canadians, for some unknown reason, are leaving the Dominion in considerable numbers and are settling on this side of the line.

- Nearly two thousand men, women, and girls are employed in the paper collar factories of Massachusetts;

- There is a dairy at Montpelier, Vermont where they do the churning by steam power;….

Boston Globe, March 4, 1872