Primary Source

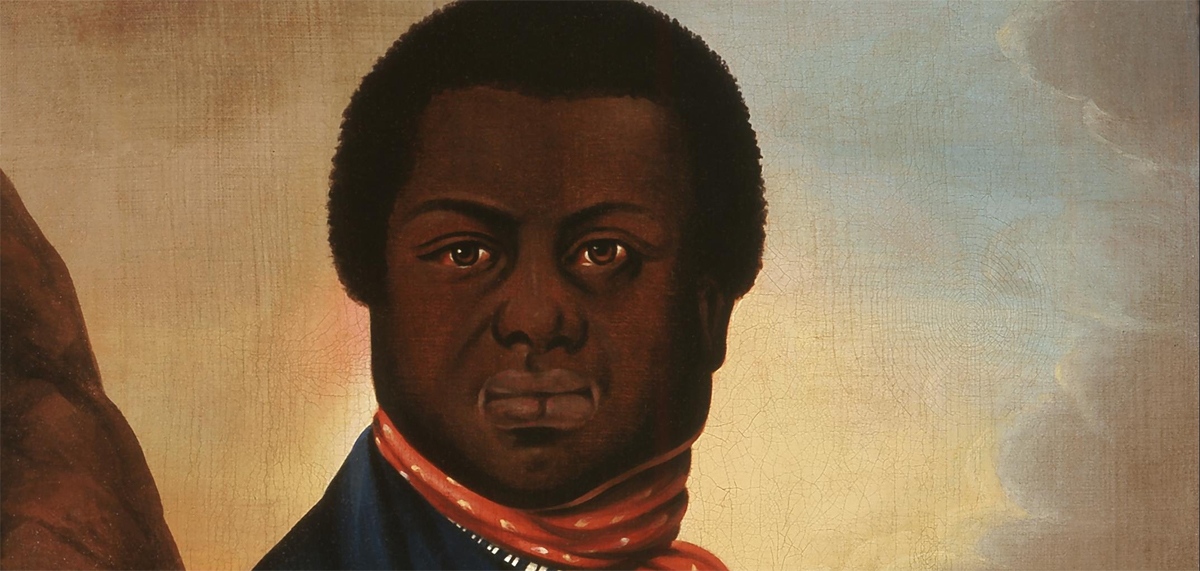

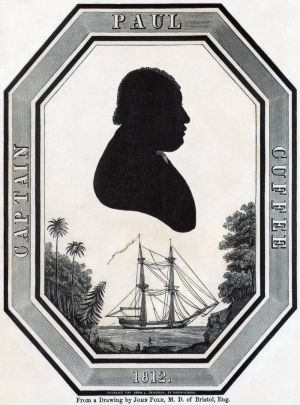

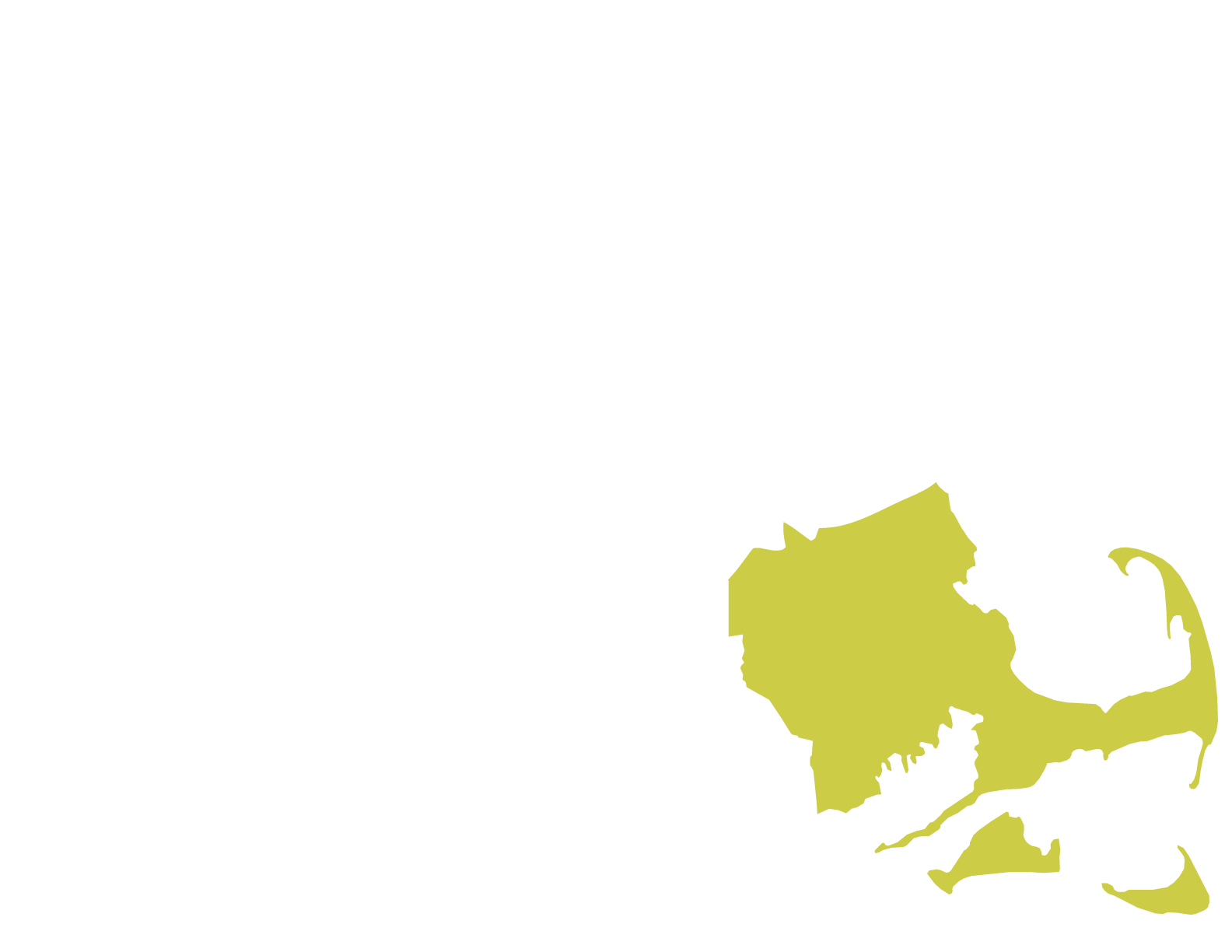

In March 1780, Paul Cuffee and six other African Americans submitted a petition to the legislature of the new state of Massachusetts.

To The Honouerable Councel and House of Representatives in General Court assembled for the State of the Massachusetts Bay in New England - March 14th AD 1780 -

The petition of several poor Negroes & molattoes who are Inhabitants of the Town of Dartmouth Humbly Sheweth - That we being Chiefly of the African Extract and by Reason of Long Bondag and hard Slavery we have been deprived of Injoying the Profits of our Labouer or the advantage of Inheriting Estates from our Parents as our Neighbouers the white peopel do. . . we have been & now are Taxed both in our Polls and that small Pittance of Estate which through much hard Labour & Industry we have got together to Sustain our selves & families withal - We apprehand it therefore to be hard usag and [one word is illegible here - ed.] doubtless (if Continued will) Reduce us to a State of Beggary whereby we shall become a Berthan to others if not timely prevented by the Interposition of your Justice & power & yor Petitioners farther sheweth that we apprehand ourselves to be Aggreeved, in that while we are not allowed the Privilage of freemen of the State having no vote or Influence in the Election of those that Tax us yet many of our Colour (as is well known) have cheerfully Entered the field of Battle in the defence of the Common Cause. . . .

That these the Most honouerable Court we Humbley Beseech they would to take this into Considerration and Let us aside from Paying tax or taxes.

Archives Division, Massachusetts Historical Society.