Primary Source

From the opening remarks made by plaintiff's lawyer Lawrence D. Shubow, October 17, 1977:

Basically, we'll be offering evidence to prove four facts. I may repeat them one more time before I am through. First, that the plaintiff is and always has been a group of Indian people: that is people of Indian ancestry, who are conscious themselves of being Indian and are recognized as Indians by the outside world.

Second, that this group of people has lived on the lands of Mashpee for hundreds of years.

Third, that the Indians on this land have made up a cohesive, permanent community with a common heritage and many, many shared ways of living, some of which carry the imprint of the past to this day, as you will hear during this trial.

And fourth, that Indian communities in Mashpee have always had their own form of organization and leadership. Sometimes it's been formal; sometimes, informal. Sometimes opposed [imposed] from the outside; and sometimes, whenever they could win the right to self-government, that leadership was chosen themselves. They've been, in other words, for 300 years—we can't prove what the situation was in 1870 without offering you evidence as to what the situation was before and what it has been since—they've been a group of Indian people living in a distinct territory in a cohesive community with their own social organization.

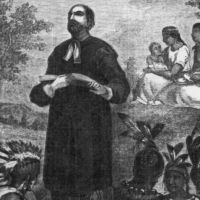

From the opening remarks made by defendant's lawyer James St. Clair on October 17, 1977, regarding Richard Bourne, a minister influential in Mashpee Indian affairs in the seventeenth century:

He conceived a group of Indians who would be Christian, who would be brought into the English system of government and would become ultimately a part and parcel of the structure of what he then believed would be an English speaking, English governed community. He conceived such a group as not being part of the Indian structure that then existed, as different. It would be English. It would be Christian. And he set about to create such a group. And the evidence will show that the culmination of this plan on the part of Richard Bourne in 1650-1654 ultimately was realized in 1870 when Mashpee became a town, an integral part of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Its members became citizens of the Commonwealth and thereafter functioned just as any other town in the Commonwealth and not as an Indian tribe.

Quoted in The Mashpee Indians: Tribe on Trial, by Jack Campisi.(Syracuse University Press, 1991).