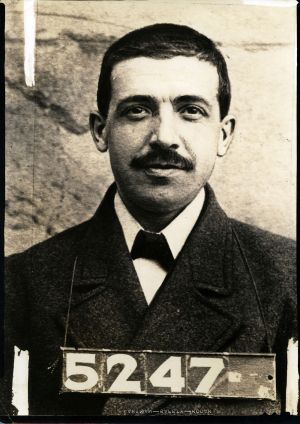

When the first notes came due, Ponzi paid them at the promised 50% rate of return. What began as a small stream of money invested in Ponzi's company soon became a flood. Each new dollar put him ever deeper in the hole. He began trying to find ways to increase his funds. Realizing that there were not enough reply coupons on earth to meet the demand, he invested in a variety of high-risk ventures. Charles Ponzi remained confident that, given enough time, he could pay back his investors. He never intended to swindle them, but he was not sure how to make good on his promises.

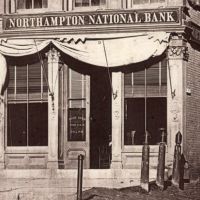

In the meantime, the press and banking and regulatory agencies were paying closer attention to Ponzi. Beginning in July of 1920, the Boston Post ran a series of articles exposing the facts and pointing out the simple impossibility of Ponzi's enterprise. State banking officials audited Ponzi. By August it was clear that he was insolvent. His company owed about $3,000,000 more than it had in assets.

Ponzi was arrested and indicted on two counts of using the postal service to defraud the public. He pleaded guilty and spent two years in federal prison. When he was released, he faced state charges. Convicted of larceny, he spent the next seven years in a Charlestown jail. A few months after his release in 1934, he was deported to Italy. In 1939 he moved to Brazil and a decade later died in a charity ward there.