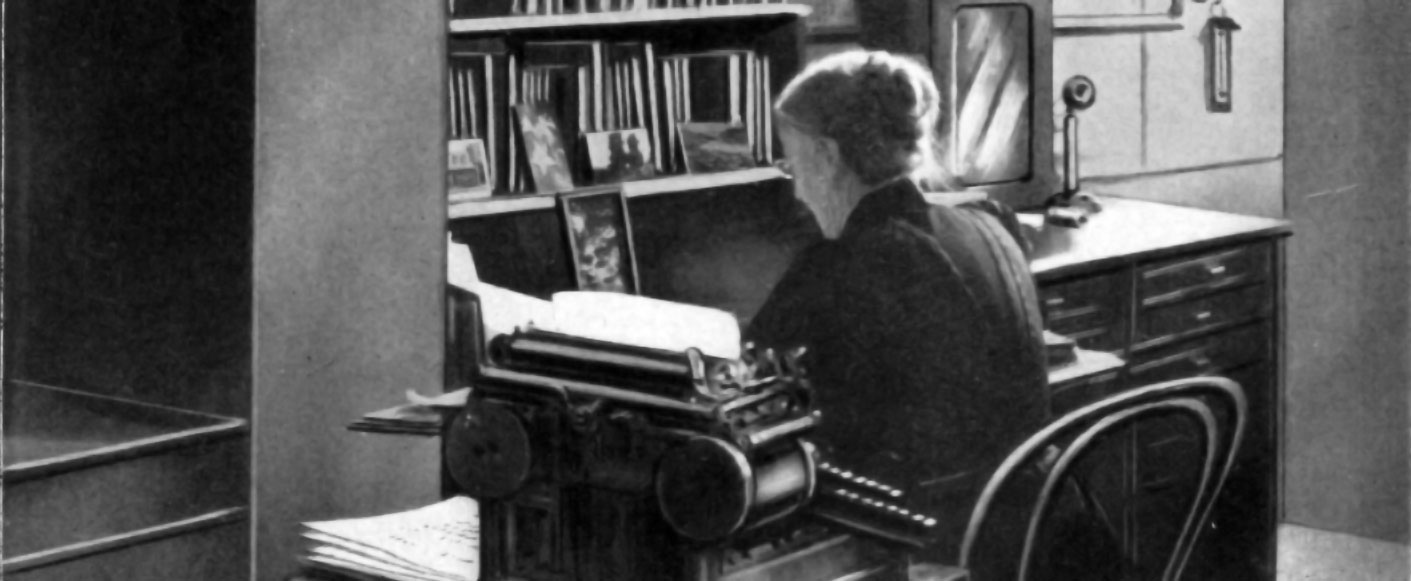

Primary Source

In this and other speeches Ellen Swallow Richards gave, she argued for the importance of including home economics in the school curriculum. She believed that teaching young women the science of housekeeping would make them both more efficient and more satisfied homemakers.

It is often stated that our educational system unfits the girls for their work in life, which is largely that of housekeepers. It cannot be the knowledge which unfits them. One can never know too much of things which one is to handle….

Can a cook know too much about the composition and nutritive value of the meats and vegetables which she uses? Can a housekeeper know too much of the effect of fresh air on the human system, of the danger of sewer gas, of foul water?…

We must awaken a spirit of investigation in our girls, as it is often awakened in our boys, but always, I think, in spite of the school training. We must show to the girls who are studying science in our schools that it has a very close relation to our every-day life. We must train them by it to judge for themselves, and not to do everything just as their grandmothers did, just because their grandmothers did it….

But if you are asking, what has all this to do with domestic economy? Everything, I answer, because if you train the young housekeeper to think, to reason, from the known facts to the unknown results, she will not only make a better housekeeper, but she will be a more contented one; she will find a field wide enough for all her abilities and a field almost unoccupied. The zest of intelligent experiment will add a great charm to the otherwise monotonous duties of housekeeping.

From "Chemistry in Relation to Household Economy," quoted in The Life of Ellen H. Richards, by Caroline L. Hunt (Whitcomb & Barrows, 1912).