Primary Source

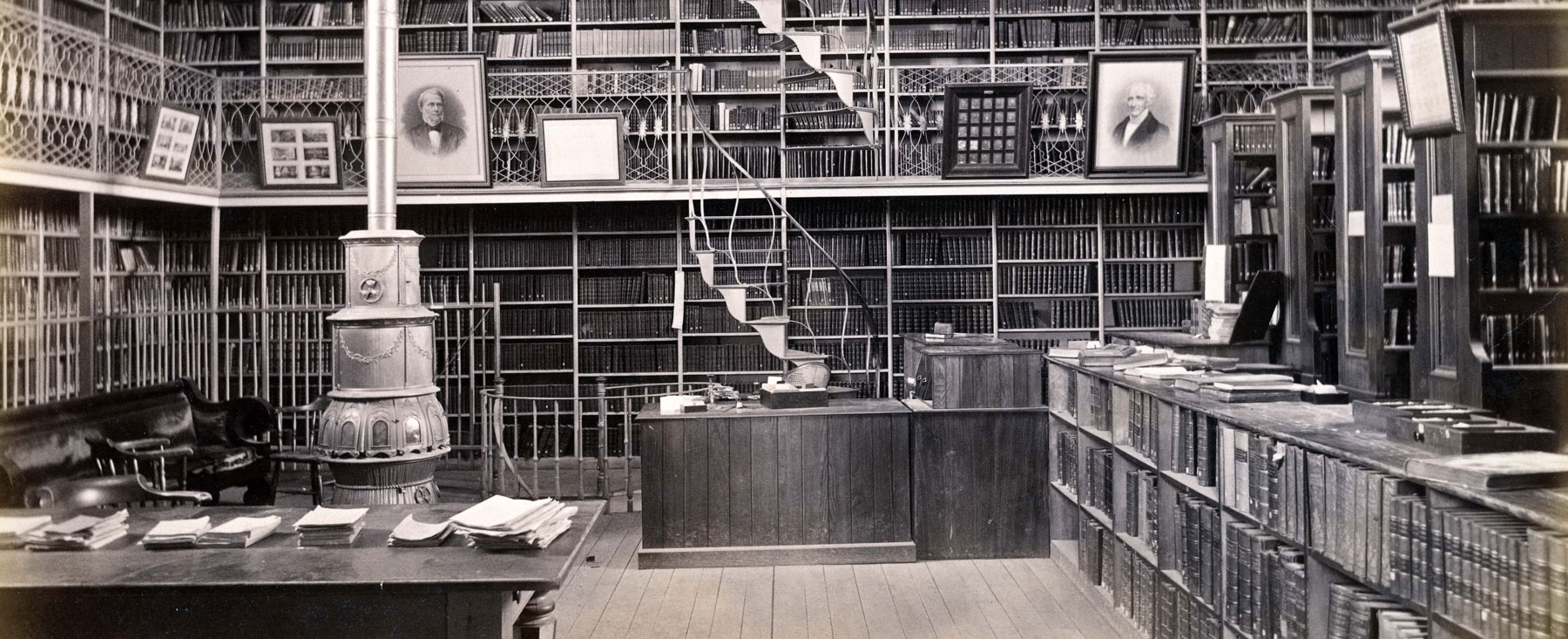

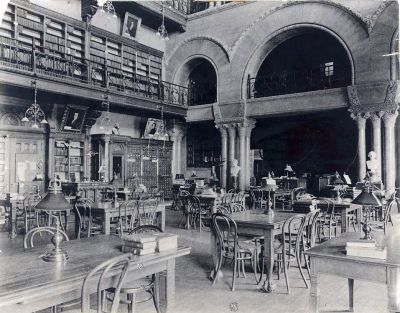

... In visiting over fifty libraries, I was astounded to find the lack of efficiency, and waste of time and money in constant recataloging and reclassifying made necessary by the almost universally used fixt system where a book was numbered according to the particular room, tier, and shelf where it chanced to stand on that day, insted of by the class, to which it belongs yesterday, today, and forever...

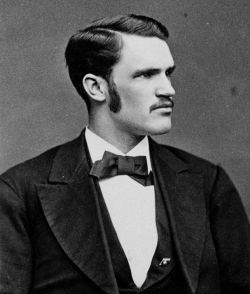

For months I dreamd night and day that there must be somewhere a satisfactory solution. In the future were thousands of libraries, most of them in charge of those with little skil or training. The first essential of the solution must be the greatest possible simplicity. The proverb said, 'simple as a, b, c," but stil simpler than that was 1, 2, 3. After months of study, on Sunday during a long sermon by Pres. Stearns, while I lookt stedfastly at him without hearing a word, my mind absorbed in the vital problem, the solution flasht over me so that I jumpt in my seat and came very near shouting "Eureka!" It was to get absolute simplicity by using the simplest known symbols, the arabic numerals as decimals with the ordinary significance of nought, to number a classification of all human knowledge in print.

Melville Dewey in Library Journal, February 15, 1920