Primary Source

TONGUES IS A CENTENARIAN

ESPERANTO VIVAS: AFTER ALL THESE YEARS

One's first impulse is to dismiss Esperanto as a wacky but harmless cause, like the Flat Earth Society or the defenders of Lizzie Borden. Only about 6,000 Americans speak the artificial language, and most of them, according to Esperanto teacher David Jordan, are "nerdy teen-age boys," the types who play Dungeons and Dragons and break into Defense Department computers. Jokes about Esperanto leap to mind: It's the USA Today of languages; it's trying to compete with English, but it's still losing to Berlitz.

And yet, in the Slater International Center at Wellesley College last Wednesday night sat 15 Americans and 20 visitors from Poland, exchanging news and gossip in their common tongue -- Esperanto. Together they ate a traditional New England meal of pektensupo (clam chowder), fazeoloj bakitaj (baked beans), and pomtorto (apple pie) and agreed that Ludwig Zamenhof's vision of world communication through one neutral, easily accessible language would yet come true. In the company of these pragmatic doctors, lawyers and teachers, the dream seemed so rational that one could almost believe it.

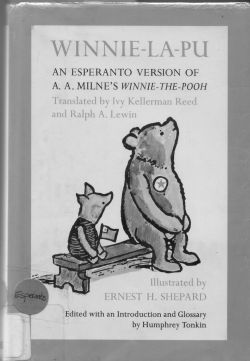

"I studied French for four years, and when I went to France, I couldn't understand anyone," said John Cunningham, a computer programmer from Millis, who brought his 13-month-old son Brandon to the dinner and periodically whispered Esperanto endearments to him. "Then I saw an Esperanto translation of 'Winnie the Pooh' in a bookstore, and I was intrigued. I taught it to myself in four months, and I understood it the first time I heard it."

Esperanto is to languages what basketball is to sports; each was invented, while their competitors developed naturally. Exactly 100 years after Zamenhof, a Polish oculist, published his first text under the pseudonym Dr. Esperanto, his creation is still eking out a precarious existence on the fringe of the linguistic world, a quasi-religious crusade to its followers, a curiosity to the rest of humanity. The best estimates suggest that between 1 million and 2 million people speak Esperanto, ranking it next to Icelandic in popularity.

In all probability, this ingenious blend of Indo-European tongues will never be widely spoken, but still it has displayed surprising hardiness and flexibility. From Cold War to glasnost, it has persisted on both sides of the Iron Curtain. . . .

Boston Globe, October 18, 1987.